|

|

Commander Carusi and his beachmasters prior to traveling to the marshalling area for the invasion of France 1944.

|

Reprinted from The Florida Times-Union with permission; Copyright © June 6, 2000

www.jacksonville.com

By Matthew I. Pinzur

Times-Union staff writer

YULEE -- Even living at the end of a dirt path off an unmarked, unpaved road in Yulee, Frank Snyder is haunted by the

apparition of a soldier clawing through the sand, dragging himself toward his blown-off leg as if just reaching the

scorched limb would restore his power to walk.

He has tried to hide from the memories of twisted bodies he could not save on the beach, but they haunt him still.

The thick marsh and ancient trees that surround his home offer no protection from the ghost of the Army officer who

waved for attention with what Snyder thought was a white baton, and he can remember the taste of his horror on

learning it was the remnants of the officer's own arm.

But if Snyder is cursed once by his inability to forget what he did on Omaha Beach, he is doubly damned by the Navy's

unwillingness to remember.

Snyder was a medic with the 6th Navy Beach Battalion, a little-known and long-ignored group of 363 sailors, who were

specially trained to land with the first waves of Allied troops on D-Day in 1944 and provide specialized services

like battlefield medicine, demolitions, communications and boat repair.

The French government presented them with the Croix de Guerre, the War Cross, and the U.S. Army has inscribed the

names of their fallen members on its own memorials at Normandy.

But for more than half a century, the Navy has barely acknowledged the battalion's existence and has ignored a

decades-old recommendation for a unit citation. Snyder moved to Yulee and began a long career as a medical technician,

but he never forgot that he was forgotten.

"Our people were some of the very first ones on the beach," said Snyder, who turned 19 the day after the invasion.

"And the Navy has treated us almost as if we didn't exist."

Survivors and their relatives said the Navy's failure to recognize the unit is a mystery, perhaps a throwback to the

thick secrecy under which the beach battalions were trained.

A unit citation proposed by the Army acknowledged the battalion's "initiative and bravery," which "contributed

immeasurably to the future success and security of the Allied Nations."

But that citation remains proposed, dormant for decades and possibly lost as long as 40 years ago. Only now is it

getting another look.

The beach battalion sailors were trained for less than 14 months before D-Day, with as much time spent learning

weapons as medicine. They were required to learn every standard Navy weapon from the .45-caliber Colt pistol to the

mammoth 5-inch cannon.

By the time they arrived in England, two months before Omaha Beach, they were attached to the Army's 5th and 6th

Engineer Special Brigades and began receiving all their orders through the Army.

"That's when they began to tell us what was coming," Snyder said. "We were very keyed up and had very little fear --

that wasn't a part of it yet."

The fear came during the 45-minute boat ride from the transport ship USS Henrico to Omaha Beach, with shells from a

nearby destroyer whizzing overhead and the ocean water already stained pink with blood. As a medic, Snyder was

unarmed. Other beach battalion sailors -- the demolitions, repair and communications teams -- carried a flea-market

arsenal of weapons, many dating back to well before World War I.

Snyder was part of the second wave of troops, landing two hours after the battle began and almost indistinguishable

from combat soldiers. Only the red rainbow on his helmet identified him as a Navy medic.

His platoon had already taken heavy casualties -- in the first wave, the commanding officer, senior enlisted man and

senior medic were all killed by mortar fire before they could step off the boat.

Approaching the beach, he could see the battlefield, choked with smoke and fire and dust and death. The first hours

were worse than any nightmare.

Snyder has studied the invasion carefully, and he quotes all manner of statistics and history to avoid clawing again

at the scab of his own memories.

The fighting was so heavy that evacuating the wounded was impossible, and medics could only carry or drag the fallen

to cover. Usually there was little they could do with such cursory training and basic equipment -- their pair of

25-pound supply bags were crammed mainly with tourniquets and bandages.

"You can only imagine what it's like to see a man with all his intestines blown out into the sand, crying," he said,

taking off his glasses and rubbing the corners of his eyes. "All we could do was give him a shot of morphine and hope

he will have one moment's peace before he dies."

|

|

|

Senior U.S. officers are watching the invasion from the bridge of USS Augusta

off Normandy. They are left to right, Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, USN, Commander Western Naval Task Force;

Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley, U.S. Army, Commanding General, U.S. First Army; Rear Admiral Arthur D.

Struble, USN with the binoculars. D-Day art of "Easy Red" Omaha Beach by Joseph Sheahan.

|

When medics became separated from their units, they began working alongside Army units. Some plucked rifles from the

sand and joined the attacking troops, rushing snipers and lobbing hand-grenades.

Landing craft that were unloading reinforcements were sometimes unwilling to stay ashore long enough to receive the

wounded, pulling up their ramps and spiriting away while Snyder and other medics stood dumbfounded, holding up the

injured in chest-deep water.

"They just didn't want to get killed," Snyder said. "We saw all kinds of bravery that day, but we also saw all kinds

of cowardice."

Even after the invading forces had pushed beyond the beach, Snyder and his comrades were working almost without sleep

to supervise the constant stream of small ships arriving with supplies for the attacking soldiers and departing with

stretchers full of the wounded ones. They far exceeded expectations for the sheer volume of supplies that crossed

the beach, averaging 20,000 tons per day, according to a Navy history of the invasion written by veterans of the

beach battalion.

"Had it not been for the skilled and dedicated men keeping the supplies flowing over the beachhead, the combat troops

would have faced a severe shortage of food, ammunition and reinforcements," according to that record, written in

1991. "These shore-based sailors have never received the recognition they deserve."

When the battalion began holding reunions in the late 1980s, veterans mingled their war stories and pictures of

grandchildren with questions about why they had become, as Snyder describes it, "an orphan between the Army and the

Navy."

Years of letters and phone calls were ignored, dismissed or lost in the Bermuda Triangle of military bureaucracy.

"All the proper paperwork was there, but there was no advocate for them back in Washington," said Kenneth C. Davey, a

high school teacher in upstate New York who has studied the beach battalions since 1993. He never knew his father,

Russell Davey, who was a doctor in the platoon that landed at Omaha Beach and was killed later in the war. He began

studying the beach battalions to learn more about his father.

"I do believe it had a lot to do with the fact that they weren't regular Navy," Davey said. "Their officers couldn't

shepherd these citations through because they had their heads blown off or were evacuated with serious injuries."

Navy officials said that because the beach battalions operated under Army control, it was the Army's responsibility

to confirm awards.

"The award proposal for the . . . [beach battalion] still remains an Army issue," said Lt. Jane Alexander. "Because

the . . . [beach battalion] was under the 5th Engineering Special Brigade, the unit citation approval was for

consideration by higher Army authority. This really isn't an issue the Navy can speak to."

Army officials, however, said neither branch is clear about what happened or who has responsibility for the award.

Responding to a request from a U.S. senator she declined to identify, Army spokeswoman Martha Rudd said the unit's

history is being gathered to present to the Army Unit Award Board.

"We'd like to take another look at it," Rudd said. "We have been working toward that."

The Navy will assist the Army in compiling historical information, Alexander said, but insists that the responsibility

lies with the Army.

But letters from 1945 suggest a different story. The commander of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, which oversaw the

beach battalion, wrote a letter to the beach battalion's commander in which he proudly announced that the Navy

commander in France, Adm. A.G. Kirk, had approved the Army's recommendation for a unit citation.

"To you personally and to the men of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, I attribute a very tangible share of the

successful establishment of the Omaha Beachhead," wrote Col. W.D. Bridges, commander of the 5th Engineer Special

Brigade. "But for this aid, the precarious situation on the beach might have been turned to disaster."

A memo that Kirk sent to the secretary of the Navy on Feb. 26, 1945, recommended that the citation be approved

immediately, saying the battalion "performed in accordance with the highest traditions of the United States Navy."

That memo, however, marks the end of the paper trail.

"No one knows what happened," Alexander said. "There's no tracking on that memo."

That paperwork should have gone through the Army chain of command, she added, but she could not explain why the

involved admirals continued to pass it up the Navy ranks in early 1945.

Elsewhere within the Navy, a medical historian is taking notice of the situation and incorporating it into a

documentary.

Jan Herman, the lead historian for the Navy Bureau of Medicine, is producing a documentary about Navy medicine in

World War II, and has promised to come to Snyder's garage apartment Monday to look through his files and interview

him about his nightmare.

When the seven-part documentary is finished -- the beach battalions are featured in the second installment -- Snyder

and Davey hope new attention will be focused on the fate of the citation.

"I really don't know what's going to happen," Davey said. "It's been 55 years, but it's unfinished business and the

obligation of this nation."

|

|

|

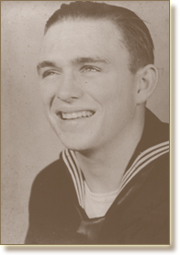

Navy Corpsman Frank Snyder, platoon B-5, before the 6 June 1944 invasion of France.

Fifty-two years later, at the 1996 Myrtle Beach, SC reunion, he presented the "Fox Green" Omaha Beach aid

station flag to B-5 medical officer Dr. Eugene Guyton. The Scuttlebutt reported that Frank had asked for

time during the 6th Naval Beach Battalion banquet for a special presentation. He stood and held a box,

opened it solemnly, and said "I wish to present this flag to the man who should have had it all these years,

Dr. Gene Guyton." It was a stunning moment and brought tears to many in the banquet hall.

|

Back to Top

Back to Top