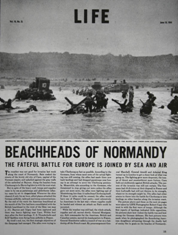

Lee Parker, M.D., takes a break on the Fox Red sector of Omaha Beach, Normandy, France. Dr. Parker's aid station is located at the bottom left of the larger photo published in LIFE magazine.

The following is an interview with Dr. Lee Parker, conducted 10 September 1999 by Jan Herman, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED). Herman has been historian of the Navy Medical Department, curator of the old U.S. Naval Observatory and, until 2009, editor-in-chief of Navy Medicine, the bimonthly journal of the Navy Medical Department. In 2009 he became Special Assistant to the Navy Surgeon General. Dr. Parker served with the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, a World War II amphibious outfit that went ashore Omaha Beach and provided battlefield medicine 6 June 1944.

Are you from Georgia? Yes, I'm from Georgia. I'm from Waycross, Georgia really. I went to the University of Georgia, and then to medical school at Augusta, and went in the service as an intern at University Hospital in Augusta.

On June 1, '43, I was assigned to Paris Island, South Carolina, for temporary duty. On July 20th, I was assigned to Camp Bradford to the 6th Amphibious Forces, and later to the 6th Beach Battalion. On the 26th of August, we went to Fort Pierce for our initial training, and then after the trip to England and the invasion, I was sent back to Fort Pierce for temporary duty, and then later to Panama City as part of the ships company down there shaking down LSTs.

When did you actually join the Navy, and why was it that you picked the Navy rather than any of the other services? Well, I've always been around the water and loved that part of it anyway, so it was just natural for me to go to the Navy. And I joined while I was interning at the University Hospital.

And that was in '43? Yes.

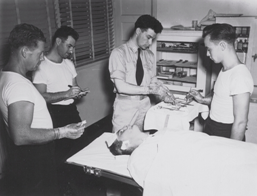

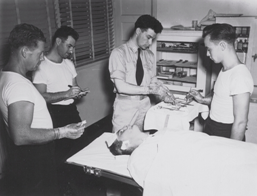

Lee Parker volunteered for the U.S. Navy soon after graduating from the Medical College of Georgia in 1942 and became active duty at Marine Barracks Paris Island, SC, 10 February 1943. Above, Dr. Parker is treating a patient and later making rounds at the Camp Lajune infirmary. Lieutenant Parker was released from active duty 1 July 1946.

And when you joined, did you receive any training or get an orientation into the Navy? No, none at all. The main thing we did down in Paris Island was looking at the blisters on the GI's feet that were marching on those hot paved parade grounds. And then we were checking swimming pools for the chlorine content and looking after safety problems there. We also were looking at the safety of the rifle range and that kind of thing. Just kind of an overseeing duty there, but no training as far as that goes. Now as far as our training was concerned, at Camp Bradford we were put in just like any Gl's. We went through the routine of daily calisthenics, the big obstacle course that everybody had to run everyday.

Wasn't Little Creek near Camp Bradford? Yes. Camp Bradford was right across from Little Creek.

How did you get selected to do that kind of training? Did they ask for volunteers? I have no idea. The only thing I can think of is somewhere in one of the forms I filled out there, I must have said that I liked small boats, thinking maybe I could get a P. T. boat or a crew or something. But, I didn't know they even made amphibious training vessels at that time. But we were put through pretty much the routine as far as medical training. Talking about special training, our special training really was getting in good physical shape and looking after general troops. And as far as any real special first aid training, we didn't have any, but we did go through a lot of drills. In fact, when we were down at Fort Pierce ...

That's Fort Pierce, Florida? Fort Pierce, Florida. There was a training base down there for the Rangers, and the Scouts and Raiders group that they had, and we were part of that. I mean, not part of it. We went in the same area. We lived in tents down there, and mosquitoes were terrible. We had to use head nets to be able to eat. You couldn't stand it.

Head nets, huh? Head nets on you all the time down there. You haven't been to Fort Pierce then?

Not recently, no. Well anyway, down there at the Coast Guard station, they had a mock up-a tall wooden scaffold up above, right along the edge of the water, and they could run an LCVP (landing craft vehicle and personnel) by the side of the cargo net. You had to climb up the top of this thing, about 30 feet, and then with your loaded gear, crawl down a cargo net into a landing craft.

At the Amphibious Training Base, Fort Pierce, Florida, Lieutenant Shortledge, holding the Thompson submachine gun with a 50-round drum magazine, instructs enlisted men at the base "gun shack" in the official U.S. Navy photo. In addition to the Navy Beach Battalions, Army Amphibian Brigades, Scouts and Raiders, and Navy Combat Demolition Units (NCDUs) trained at Fort Pierce. The NCDUs in Operation NEPTUNE were attached to the U.S. Naval Beach Battalions for administrative purposes. The beach battalions were naval elements of the Army Engineer Special Brigades for the invasion of Normandy.

Then you'd go out through the jetties and get out there and circle until everybody got seasick. Then you ran into the beach and dug a foxhole and sat around until it's time to go back home. But the main thing was getting used to the landing craft. We always had to walk back. The Corps of Army Engineers that were down there along with us always had transportation, but we had to walk back from the beach every time.

So the initial training was at Fort Bradford, and then they sent you down to Fort Pierce. That's right.

How long were you at Bradford? From July the 20th to August the 26th, and then we ended up going to Lido Beach, in Long Island. And that's where we were shipped out on the Mauritania II.

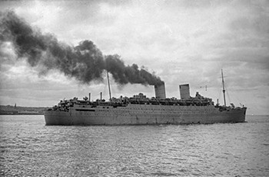

In other words, it was one of the larger luxury liners being converted for a troop carrier. And we loaded on that thing and Admiral [Harold R.] Stark was aboard, and we started out backing out of New York harbor and got out there in the channel doing an abandon ship drill.

You had a collision didn't you? Yes.

I remember the Mauritania had a collision on that first run. That's right. The tanker came across from the New Jersey side and rammed that thing right in broad daylight. So we went back into port and they welded plates on that thing and then we took off. But, going across, we didn't have any escort because we were too fast.

Admiral Harold R. Stark, head of all U.S. Naval forces in Europe, was aboard the Mauritania when she set sail from New York City. Nevertheless, in an 8 January 1944 V-MAIL to his wife, Dr. Russ Davey wrote, "Well, as usual everything happens to the 6th Beach Battalion. We had at last apparently got under way and were just about heading for open sea when, during our first Abandon Ship drill, we ran into an oil tanker. Not much damage was done to either ship but because the Pilot was still in command of our ship, he had to put back to port to report the incident. So here we are, back in New York harbor, tied up to the same dock which we had left but a few hours before. I believe that the damage has been repaired by now and we hope of shoving off soon again. It was certainly a strange and almost unbelievable sight to see two large ships approaching each other at right angles, both ships refusing to give way to the other. We all could see that they must collide but couldn't believe such a thing possible. However, it did happen and I'm glad to say that our ship, being the larger, rolled a lot less than did the tanker."

Do you remember anything about the voyage itself? It was rough, very rough. I mean, we went into some rough seas, but other than that, we didn't run into any problems at all.

Probably wondering about getting torpedoed or something. No, of course they had constant lookouts and all that stuff, but we didn't run into any trouble at all.

That was a pretty fast ship though. It was full size, above average.

I want to just take you back just a second. When you were at either Bradford or Fort Pierce, did you get any weapons training? Yes, we got a lot of training. We got regular infantry training. When we were at Fort Pierce, we went down to the rifle range at West Palm Beach, the Army rifle range there. We were trained in .45s, the carbine, and the regular Springfield rifle.

Not the Garand but the old bolt action '03 Springfield. That's right. And then later when we came up to Bradford, they put us through fire controls when we had time. We'd go over to NOB [Naval Operating Base], Norfolk, and go through their fire control systems, and then through gas drills, where they put you in there with tear gas and let you taste a little of that.

And then we went out to the gunnery range, right there on North Virginia Beach. Right out there on the end they had an anti-aircraft school. We went through shooting 20 mm and 40 mm cannons, the anti-aircraft guns. So we were shooting at Navy socks. They were flying those socks behind planes, so each one got to shoot at those.

Being that you were a physician, you still hadn't gotten any kind of specific medical orientation? No, no.

They just figured you already knew that stuff? Yes, that's right.

After its adoption in 1941, the M-1 Steel Helmet became the symbol of U.S. military forces and was used world-wide by all branches of the services for the duration of World War II. Above are identical images of Seaman First Class Irving Goldsmith's M-1 combat helmet in color and black & white. The Navy Beach Battalion "red arc" is virtually obscured in old black & white Omaha Beach photos. The distinguishing "white arc" of Army elements of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade is quite prominent in black & white.

So then you went up to Lido Beach, and was there any additional training at Lido Beach? No, there was just a matter of waiting for transportation. Finally, they put us on a train and carried us down to New York.

I guess you probably went up to Long Island City and then they took you across to Manhattan. It was a big resort area up there. We were staying in a big golf complex up there at Lido Beach. I think it was a resort hotel but I don't remember any additional training.

Were you assigned to a unit at this point? Did you know that you were in this 6th Beach Battalion? Yes, I did. When we left New York, we were in the 6th Beach Battalion. I was assigned to A Company, the 3rd Platoon, A-3.

This was the first time then, when you left Lido Beach, and you started heading over to Europe, this was when you were assigned to this unit? You hadn't been assigned to any unit prior to that? Well, I don't know exactly know when that designation took place. I guess it took place down in Fort Pierce. But we were working together that way. Dr. Frank Ramsey was one of them, and Jack Daughtrey and I were in "A" Company.

Jack, what was his name, Jack? Daughtrey. He was from Atlanta originally, and he came back and practiced surgery down in Lakeland, Florida for awhile, before he died. Frank Ramsey was hit on the beach going in. But as far as when we were designated, I'm not exactly sure of that.

But it certainly was by the time you were on the Mauritania though. Well, yes.

You knew what unit you were in. Did you have any idea what you were in for at that point? No.

Probably nobody did. Probably not.

So, the crossing was relatively uneventful except for that little collision at the beginning. The collision at the start, that was it.

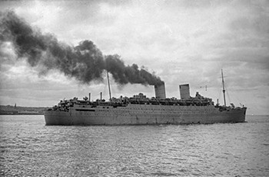

Mauritania II sailed on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York 17 June 1939. On her return, she was requisitioned by the Government, and later armed with two 6-inch (150 mm) guns, painted battleship grey, and by December 1939, dispatched back to America. For three months the ship lay idle in New York, docked alongside the Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary, and the French Line's Normandie. During World War II, the Mauritania traveled 540,000 miles (870,000 km) and transported over 340,000 troops, including the 6th and 7th Naval Beach Battalions. She was often tracked by the enemy and had to evade concentrations of U-boats that were known to be lying in wait for her. The Mauritania docked in Liverpool 17 January 1944 and the beach battalions were transported to Salcombe, Wales for advanced amphibious warfare training. After the war, the Mauritania made several further voyages for the Government repatriating troops.

And then you had to go back in for repairs I guess. Well, they pulled her back in and welded plates on the front of her all night and the admiral got back on the next day and we took off early the next morning.

So you probably slept in hammocks or something on the way over. No, actually I was in a stateroom that had been shored up. They had put in some 4 x 4s for a series of bunks and we had a bathtub in that unit that was big enough to swim in. It was luxury quarters at the time, but I think there were six or eight of us in there when we crossed over, so we had real bunks.

I don't know how the crew slept because they looked after themselves. I didn't go down to see how they were, but they weren't too unhappy about it. When we got into that real rough water, we lost a lot of plates and all that stuff. In the galley there was stuff just sliding allover the dining room.

So there probably was a bit of seasickness going over. Well, there was some, yes.

What was it, about a 12-day trip over there, or less then that? It wasn't that long. I don't remember, but it wasn't that long; it didn't seem much more than 2 or 3 days.

Where did you land? I don't even remember that. We took a train from there to; I guess we went there straight to Salcombe, in Southern England.

Where was it? Salcombe. And that was at the very southern tip of England. It's kind of a summer resort area down there, near Slapton Sands Beach, if you're familiar with that.

This 6th Naval Beach Battalion officer photo was taken in England and published in Jonathan Gawne's Spearheading D-Day: American Special Units in Normandy (1998). Content in the paperback version above is identical to the original hardcover book. In a 10 April 1944 V-MAIL to his wife, Dr. Davey wrote, "I don't think I told you about the Co- "C" officers having our picture taken the other day. It was a real old studio and the photographer wore a smock, torn, and large flowing black bow tie—just like in the funny papers or the movies. He had a very old camera, and something happened which I have never seen happen, but have read about and joked about many times: Just as he took the first picture, two of the lenses immediately fell to the floor and rest of the camera seemed to fall apart. In other words, we literally broke the camera when our picture was taken. It took him half hour to get it back together again, in order to take another picture—this time without mishap. The pictures are to be ready in two weeks; I'll be sure and send you one."

Oh yes, I've heard about that. Well, we were near there. I know I went on two or three occasions, I was assigned to an LST on temporary duty. A driver would drive me up to Weymouth, and I'd board an LST as a physician, since that particular boat didn't have a physician and they would have combat troops come aboard to land on the beach. And they just wanted that additional help. So I would go up, get on that, make an invasion, just as ship's company. When they came back, a jeep would pick me up and take me back home.

Who did you report to? Who were you taking orders from at that point? I don't have any orders that show it, at all. I've looked through my orders, and nothing shows it at all. It was just probably telephone communication between CDR [Eugene] Carusi and whoever were the powers that be.

And CDR Carusi was the head of the unit? Yes, he was. I'll tell you, we were in a mess at first. When we first organized, we had a hot rod lieutenant who thought he was something, and then we ended up with a commander. His only previous training was with the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) camp, and he didn't know anything about the rules and regulations... And finally we got down to Fort Pierce, and Carusi came on and a fellow named Reardon was with him, and then we were finally commissioned down there. We didn't have a table of organization or anything to go on until we got down there. It was a bastard outfit.

Before we left Norfolk, we had a supply fellow that was with us. One night at a bar, he ran into a buddy of his who was running part of the naval ships stores over at Naval Operating Base Norfolk. He told him, come over, he'd get anything he wanted. It would be just like turning me loose in Home Depot with a cart and a trailer, and picking up anything you wanted, and that's what he did. He picked up stuff.

Navy Beach Battalion sailors training for D-Day and Dr. Davey's invasion equipment. The New Yorker war correspondent A.J. Liebling described 6th Beach Battalion personnel as "sailors dressed like soldiers, except that they wore black jerseys under their field jackets; among them were a medical unit and a hydrographic unit. The engineers [Army 5th Engineer Special Brigade] included an M.P. detachment, a chemical-warfare unit, and some demolition men. A beach battalion is a part of the Navy that goes ashore; amphibious engineers are part of the Army that seldom has its feet dry."

He called back and told him, "Send me six, 6 x 6 trucks. I've got some stuff to bring over there." He had dishes, plates for the officers mess, he had signal flags that would go on a battleship; they were too big for anything else, and he had foul weather gear that you wouldn't believe--masks, goggles, fleece-lined jackets, boots, everything.

They started writing about it. When we came back up Norfolk, I asked CDR Carusi, "How did you ever get out of that mess." He said, "Well in the Navy, you just write a lot of letters and then you get them all together. Then you find that file and you get rid of that file." And that's what he did apparently.

A real operator, huh? We operated on that basis. There was a young lieutenant that was head of communications for the Beach Battalion, Howard Semple. Howard was a drug salesman... Anyway, he procured a lot of stuff, and I enjoyed going with him. We would get stuff like ... For instance, when we were in England just before the invasion, they assigned us about four jeeps and they told me to go down to Weymouth to the Navy shop and get some stretcher racks put on it.

I didn't know what a stretcher rack looked like for a jeep, but we went down there and the Navy figured it out. They put them on the front and the back-metal 1-inch square angle iron and they just welded it all, custom built but they figured it out.

Howard found out by talking to the communications officer that on some of these APAs -these assault transports - that they had some spare radios. I think it was a 6-10 or something, which was a lot better than the little hand held stuff that they were going to let us use on the beach.

So we took a jeep and we found a generator and put that thing on a drive shaft of a jeep, had it fixed up with a typewriter and about four different radios on that thing. But when we got to the beach, one of the fire control officers from the Texas (BB-35), which was sitting right off of our beach there, firing those 14-inch shells across us, came by and said he needed it because he lost his communication.

So he took that and went on up in the hills, and directed fire with that thing. They normally used blinker light and signal flags. Of course, originally it was battery operated. Well, the battery doesn't last long when you run it 24 hours a day. So we ended up with a generator and then we were always trying to get gasoline for that thing. The communication was fun. I enjoyed watching them get it all together.

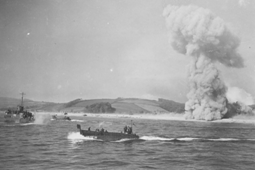

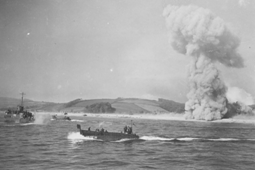

"Attack on Slapton Sands" watercolor by Dwight C. Shepler and U.S. Navy photo of training at Slapton Sands, Devon, England. Slapton Sands is best known as the tragic scene of Operation Tiger, a huge practice run in preparation for the D-Day invasion of Utah Beach in Normandy. Early in the morning of 28 April 1944, nine German E-boats spotted a convoy of eight LSTs carrying vehicles and combat engineers of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade and attached 2nd Naval Beach Battalion. The Allied convoy was attacked resulting in the deaths of over 600 American servicemen. There was additional tragedy when 308 men died from friendly fire.

What do you recall about your stay in England before the invasion? I'll tell you, it was kind of like something you dream about in a book. But we went to a lot of real top secret meetings in old churches. The heads of each department were there. General [George C.] Marshall came by one time and had the MPs, the heads of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, which we were attached to. And they had sand table models for you to look at - exact duplicates of the beach.

And they told you right quick that when you got there, there was not going to be anybody to tell you what to do.

So at this point, the 6th Beach Battalion was attached to this Brigade? To the 5th Engineer Special Brigade.

The 5th Engineer Special Brigade. That was Army? Yes. That was their assault troops that were to come inland prepare the beach and maintain the operation. And they had a medical officer with them and some corpsmen there. We worked together real well, did a good job. We were later sent up to Swansea, Wales, to play with the bulldozers up there. We learned to drive bulldozers so, if one of them broke down and got in the way, we could get it out of the way. And that was fun.

At one time we were near some combat troops of the First Division. When you sat down and listened to some of these boys ... They had been in Africa, Sicily, and Italy, and they were very confident. And we went to watch them do their little thing about how they approached a pillbox and set their satchel charges on them. So that was part of our training, to watch them operate.

And then as far as the engineers, I don't know of anything special except just going through the routine. At one time, they inspected our rifles and it was quite embarrassing. A lot of our rifles, you couldn't even see through the barrel.

Inspecting the Normandy beaches, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel developed the three mile deep defensive "Rommel Belt" along the coast of France. Rommel said, "I want antipersonnel mines, antitank mines, antiparatrooper mines. I want mines to sink ships and mines to sink landing craft. I want some minefields designed so that our infantry can cross them, but no enemy tanks. I want mines that detonate when a wire is tripped; mines that explode when a wire is cut; mines that can be remote controlled, and mines that will blow up when a beam of light is interrupted." The Germans effectively used sea mines, erected all sorts of beach obstacles with attached explosives and numerous guns in bunkers sited from different angles on every stretch of the beach.

Were you issued these weapons at Lido Beach or when you got over there? I guess I was issued a .45 in this country, because medics didn't carry .45s in the European theater as they did in the Pacific. So it must have been then. I carried one for, sometime after we got to England, and then we turned them in.

And then they took them away from you? Yes.

Then, during the invasion, you didn't have a side arm. No. I had plenty around me though. In the evacuation station, I was sure there were a few things around that I could get my hands on.

Did you know, at this point, what your role was? Now here you are attached to the 6th Beach Battalion which is attached to an Army Brigade. Yes, our role was simply to look after the casualties on the beach, theoretically, up to the high water mark, and evacuate them. But that didn't mean anything. Our main thing was to evacuate casualties, and that meant loading them up on small boats, and trying to get them out.

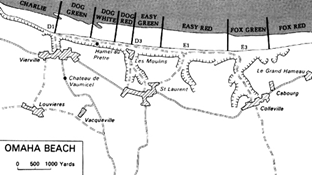

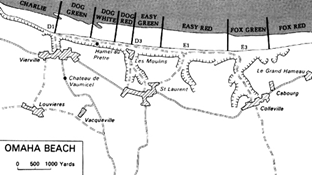

Now the bad part about it was, we ran into some bad weather. During the evacuation process, there was a road of exit on Fox Red Beach. Our beach was Fox Red. Looking at the beach from the water, it was extreme left. I landed on Easy Red, which was right in the middle of the complex, and moved laterally.

From left to right? From right to left.

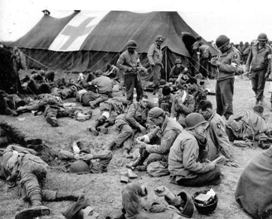

As tensions of the anticipated invasion were building in the United States, the Pentagon assured the nation that no efforts would be spared in caring for the casualties. In the May 22nd issue of LIFE magazine, in a photo spread titled American Invaders Mass in England, casualty predictions were signaling to the American people that D-Day was near. Battle wounded on the far shore would initially be evacuated back to England and later returned by hospital ships to U.S. ports in New York, Boston, Charleston, SC and Hampton Roads, VA. Hospital trains in the States would be carrying two hundred patients each, accompanied by doctors and nurses. American crews were being trained to lift litters through sleeper-car windows with a minimum of jostling. For security reasons, the public was unaware that 27 Navy doctors and 216 hospital corpsmen were scheduled to be on the invasion beaches to care for the initial wounded and the USN Beachmasters would then arrange for seaward evacuation. Prepared to receive heavy casualties on 90 LSTs waiting off the Normandy coast would be 355 Army and Navy trauma surgeons assisted by 2,520 hospital corpsmen and medics.

Let me take you back to England for a little bit. You now are attached to the Brigade. You knew what your role was going to be and you were probably starting to get some idea as to what was going to be going on, that you were going to invade something. You didn't know where, but you knew that something was going to happen. And there was lots of activity going on. When would this have been? When did you arrive over in England? Would that have been in maybe April or May of '44? I don't even remember when we left New York, to tell you the truth. But anyway, I ended up getting on board the Dorothea [L] Dix [AP-67] on June the 2nd.

The Dorothea Dix? Yes.

What was that, an AKA [troop transport]? Yes. And Ernest Hemingway was aboard that ship at the time. And I rode it across the Channel. I went up top and watched them cutting mines loose with mine sweepers. They had riflemen up there shooting at them, blowing them up as they went. The mine sweepers were ahead of you and they were cutting them loose with their nets.

What port did the Dorothea Dix leave from? Weymouth.

There was a false start as I remember. You left and had to come back because of the bad weather, and put it off for a day. Well, we didn't leave that time. They started off on the 5th and the LCIs and the ships that were slower took off before the cancellation and then they had to come back in. But the Dorothea Dix stayed inside of a big harbor there that had walls around and an entranceway into it, so it was well protected.

The LCIs, Ernest Hemingway wrote, "were the only amphibious operations craft that look as though they were made to go to sea. They very nearly have the lines of a ship." A.J. Liebling was aboard the USCG-manned LCI(L) 88, a 155 foot long / 300 ton Landing Craft Infantry (L)arge. This was the initial LCI of the 4,000-ship invasion armada scheduled to make a landing on Omaha Beach. (Cross-Channel Trip)

But we went into what was called an area of debarkation, a marshaling area. Sometimes, if you think about it, you might see if the Coast Guard has a picture of the Beach Battalion after they left Salcombe going to Weymouth, because I think it was the Coast Guard that made this picture. It was a big roadside picture of the whole Battalion and I have never tried to find that.

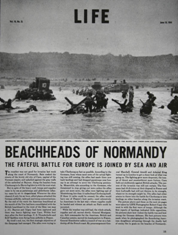

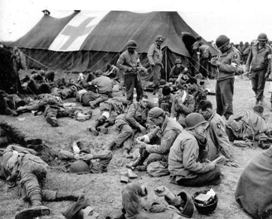

I did get some stuff from the Coast Guard later, but the beach we were on during the invasion is one of the popular ones in Life and Time magazine. It was a big picture and it showed my evacuation station, so called, on the beach. [see photo at top]

On the beach, and I'm getting you turned around I know, but we had a 14 x 14 pyramidal tent set up right on... As you come up the beach there's a dune, a little rise up there where it gets off level. There's a sand dune there, and we just had it by the side of the road. In other words, all it was a place where we kept our beach bags full of plasma, our serum albumin, and battle dressings. And we had a table in there that you could put them up on the stretcher and work on somebody level, like an operating room. But we weren't prepared for that, and our first aid stuff consisted of what we carried with us.

When we left the marshaling area, I found a guy that was going to drive the bulldozer for the Engineer Special Brigade. I cornered him and talked to him a little bit, and told him that I had a bunch of steel stretchers and there was no way that we could carry them by hand. One man could carry one, but they were heavy. And they had different kinds. They had some wooden ones that folded up, but they were still heavy. So I asked him if he would let me tie them on the front of his bulldozer blade? And I stole a pair of wire cutters, and got some steel banding material, and we stacked a bunch of steel litters across the blade of the bulldozer. And I strapped them on and gave him the wire cutters, and I said, ''Now you're going to be out there in the open. I've got some Navy bags that carry about 25 blankets in a bundle, and I'm going to give you about three of those and let them tie them around you up there, and you'll have some protection. When you get to that beach ... He had the map, the same ones we did, I said, "This is where I'd like to have them." And damn, if he didn't put them there the first day.

He took the blankets and he... Yes. He tied those up around him so he had a little protection. But when he got there, he dumped those stretchers in one pile and threw the blankets there with them.

In the above 6 June 2004 photo shot by Allen Sullivan of the Athens Banner-Herald, Lee Parker displays invasion gear including his BIGOT map. In the BUMED photo, Dr. Parker and Jan Herman are walking among American graves at the Normandy cemetery above the beach where the 6th Naval Beach Battalion went ashore on D-Day. BIGOT is a security classification higher than Top Secret. Those "BIGOTed" knew the secrets of D-Day. Everyone with knowledge of D-Day - location of landing beaches, time and date of the invasion, low vs. high tide, etc. - were security cleared and listed on what was known as the "BIGOT list." Headquarters, Beachmasters, and medical officers of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion were "BIGOTed." Those on the BIGOT list were banned from traveling outside the UK in case they were captured and coerced into talking. There was one exception - Churchill himself!

Were you able to find them? Yes, they were right where I wanted them because - we had a designated spot. We were classified as BIGOT. Do you know what that designation means?

What was that again? BIGOT. B-i-g-o-t. It supersedes more then secret. In other words, you're given these if you're going in the invasion. And they had all the critical maps. The information, and for some reason, I kept them. I have them. I sent a lot of them up to Ken, but he didn't realize we were in a BIGOT designation there.

In fact, I tell you how important that was. When they had that deal off of Slapton Sands where they lost about 750 people, there were a couple of LSTs that were in that thing, and they went down and they were loaded with DUKWs--amphibious trucks. So that was a big loss because they were part of the real plan.

So they even sent divers down after to search, to be sure that they didn't have any BIGOT information aboard, which was all, except the exact time of the operation. It told when, where, and all that stuff. So we had maps showing the beaches and they had a stereo photograph made.

A stereo photograph? Of the beach. They flew along that with a P-38 before the invasion, and had this color photograph made of the whole beach area. And then you could put on these green and red glasses and look at it. If you knew what you were looking for, you could find all the church steeples and all that were landmarks going in and you could see them. And they were just like they were because, as we were going in, you could see all the stuff.

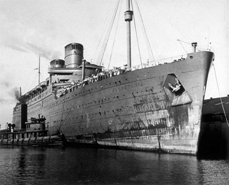

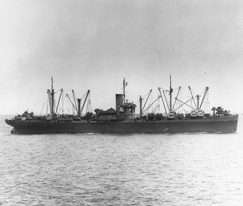

USS Dorothea L. Dix and "In Transport Area" artwork by Alexander Russo. The Dorothea Dix, that provided cross-Channel transportation for Dr. Parker and his corpsmen, was a 11,625-ton transport built at Quincy, Massachusetts in 1940 as the merchant steamship Exemplar. From April 1941 to April 1942 she was the British flag freighter Empire Widgeon and, a few months after her return to U.S. custody, was taken over by the War Department and converted to a transport. The ship was transferred to the Navy and placed in commission as USS Dorothea L. Dix (AP-67) in September 1942. In April 1944, the Dorothea L. Dix began training in British waters for the invasion of France. During the Normandy operation, she took part in the 6 June 1944 landings on Omaha Beach. The transport then returned to the Mediterranean Sea, where she landed troops as part of the invasion of southern France in mid-August, and shuttled more combat forces from Italy to France over the next few months. (Department of the Navy - Naval Historical Center)

You recognized it immediately. Oh, immediately, yes. But we went into Fox Red. [Dr. Parker went ashore Easy Red, and moving right to left, led his corpsmen through Fox Green to his assigned beach, Fox Red]

You mentioned just a few minutes ago that you had serum albumin. Did you have individual kits? The plasma is just like it is now. You had two units. There was this distilled water that went in to liquefy the stuff and there was a powder of the plasma. So you had to put them together. They were vacuum packed. You had a two-way needle you stuck in the water, then stuck it into that plasma, and it just drew itself in there. Then you had that plastic tubing to go with it. But we mixed our own before we left the Dorothea Dix. We mixed our plasma. But the serum albumin was by itself. I mean, it didn't require mixing. I had not used it before but we used a hell of a lot of it.

It was packed in some kind of little cans as I remember. Yes. And had a tubing on it. Our supplies were handled by beach bags, and beach bags were simply two waterproofed trash bags. They were a little heavier grade then a trash bag, but they were filled with battle dressings, morphine, sulfa, sulfanilamide tablets, and the serum albumin and the plasma.

Did you have suture material and that type of thing? Well, there had to be some. We had a few of them, but that particular stuff wasn't too much needed. Ken had or I had a list somewhere of what a beach bag contained, and I don't know. I haven't run across that recently.

Every Navy Beach Battalion platoon was assigned 25 "USN" beach bags, each containing 25 syrettes of morphine, 30 triangular bandages, a half-roll of cellulose bandage, 12 cotton swabs, 30 large battle dressings, 20 small battle dressings, 2 rolls of adhesive tape, 1 package of basswood splints, 3 tag books, 2 plasma units, and 10 packages of pulverized sulfa. Going ashore on D-Day, Dr. Davey (height 5'5") dumped his personnel backpack into the Channel to avoid drowning and safeguard his medical equipment, including 10 Units of Plasma, which would be greatly needed on the beach.

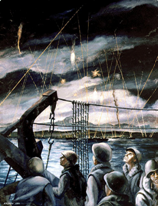

So when you were crossing the Channel on the Dorothea Dix, what do you remember about that crossing? You'd said something about seeing a lot of signaling going on and the minesweepers. Well, yes. The mine sweepers were ahead of us and the smaller boats that were slower than we were, were ahead of us, the LCIs and that kind of thing. When I got up on top of the Dorothea Dix, up on the flying bridge, and I managed to get up there, as far as you could see, to the front of you, to the back of you, to the right, to the left, you didn't see anything but ships. And then when you looked overhead, there was nothing but planes with black and white stripes on them. They did that to designate them, because during the Sicilian operation, they shot down a lot of their own planes. So for this one, the wing markings on them were either the P-38s with the twin tails, or the big black and white stripes on the planes designated them.

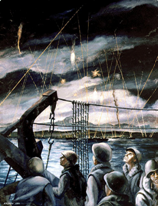

We had every gun on board those transports. I don't know if you've been aboard one of them, but when it was combat loaded, it had all the gun emplacements. Most of them were 20 millimeters. And there were a few 40 millimeters, and some were quad mounted. Some of them were twin mounted and they had their own crews. And when they went to battle stations, which they did when we left England, they were fully manned and they had first aid kits on each one of those. At night, down on the beach, after we got on the beach, when anything that even sounded like an airplane came over, it was like the 4th of July. Everything lit up. And every other shell was a tracer, so it was quite scenic looking.

What did you see when you approached the Normandy coast? Well, the Dorothea Dix was anchored about 10 or 12 miles offshore, so you didn't see anything. But we were supposed to have gone in on the second wave. My group started off at 7:30 that morning, or 7 o'clock. They loaded up and went in.

The first boats that came back brought wounded with them and we brought the wounded aboard. Then we were supposed to go in on an LCVP, which is the smaller of the landing craft. But they canceled those and put us on an LCT. And we started off.

The 14-inch guns of the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36) open up on the Normandy coast and the USS Arkansas (BB-33) "Opening the Attack" watercolor by Dwight C. Shepler. Hit by 1 aerial torpedo and 6 or more bombs during the 7 December 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, the USS Nevada was beached in the harbor entrance to prevent sinking. Resurrected, she returned to combat and her guns were actively employed during the 1944 Normandy Iandings.

Did you have to go down the cargo nets to get in them? Yep, we sure did. And it was rough but we didn't have any casualties getting in there, but we were crowded in that thing because they put several boatloads in that one LCTL. It was a pretty big boat and started in the beach and we got close to the beach and they told us to get out of there.

We were watching boats go down, hit. They had an LCT loaded with nothing but blankets, Army bedrolls. They were just blankets rolled up and tied together. They looked like a bunch of cord wood. That thing got hit and it went down slowly and those blankets were all floating out there. They had blankets all over the place. We were picking up people from different boats before we got in. When we hit the beach it was fairly low tide, so we had a long way to go.

How far out were you when they dropped you off? I was able to hit bottom and come out of there.

So it was up to your neck then? Oh yes, it was up to my neck. And I was dressed in these gas impregnated coveralls. They changed gas masks on us just before the invasion; they got a new model. We each had a gas mask and we had our shoes impregnated with some BAL so we wouldn't get any blisters from mustard gas.

What was it? BAL ointment. You rubbed it in your shoes like you would some linseed oil, and then we were dressed with our paratrooper boots and fatigue clothes, and a combat jacket, they called it. It was just a regular windbreaker.

And a helmet of course. Oh yes, and a helmet.

What was that? What did that look like? Well, it had an arc across the front of it

For U.S. joint amphibious warfare on Omaha Beach, the Navy Beach Battalions painted a "red" arc on their helmets and the Army Engineer Special Brigades painted a "white" arc. Note the small white oak leaf signifying the Navy Medical Corps and the blue-grey band painted at the base of Dr. Davey's helmet. Each beach battalion platoon was assigned 5 medical cases; C-8 platoon's "Case No-4" above typically contained Distilled H2O, 5 Syrettes M.S. (745 Morphine Surettes per medical section), Boric Acid , Arom Spts Amm., Tr Iodine (antiseptic solution), Applicators, Elastic Band, 2" Band Gause, Flashlight Batteries, Cotton Abs., Large Battle Dressing, Gauze Compress, Surgical Gloves 8½, Muslin Band., Safety Pins, Adhesive, Bass Splints, Hypo Syringe 2cc & 10cc, Tourniquet, Tongue Depressors, Bottle, Flashlight, Hand Towel, Skin Pencil, Soap, Diagnosis Tag Books, Tr Green Soap, Zink Oxide ointment, 10 Brandy Bottles, Coramine, Det. Emuls., Sulfon Pulv., Procaine (Sp.), Talc, Thermometer, Pus Basin, 3 1/3 Phenol, Suture, Gut, Water Proof Matches, 100 tabs. Aspirin, 6 Amps. Sodium Pentothal, and Can Opener. "Case No-5" carried ashore by the platoon M.D. contained 10 Units of Plasma.

In red wasn't it? Red, and then it had a gray band around, about 2 inches around the whole helmet. That was to designate that you were supposed to be on that beach... And then, on the back of your helmet, if it was an officer, it had a white line down the middle of it in the back. And they [Army] had an amphibious seal in the middle of that arc.

An amphibious seal? Yes, the amphibious seal, with the anchor and rifle, or whatever it is. I've still got my helmet.

Were you dressed any differently then the Army people or did you look pretty much the same? No, just exactly like the Army. We were fed by the Army and I think they maintained us while we were on the beaches as far as food because we all ate ten in one rations and we ate pretty well.

Who was your superior officer when you went in on the beach? Did you report to someone specifically? Commander Carusi was our commanding officer, but we didn't report to him. In fact, Frank Ramsey, who got hit on the beach, was our senior medical officer. So, we didn't have him to report to. We reported really through the Army. They had a good communication chain. They had telephones land lines.

Radio communication, as far as I was concerned, was limited ship-to-shore. Our platoon leaders were beachmasters. They were the ones that supposedly controlled the beach, and if they got a special order for stuff they would order a certain type of ship in.

A 6th Beach Battalion detail helped rescue two platoons of infantrymen from the Channel. These men had debarked in deep water and their load of equipment was pulling many down. "We lost many men to bullets but also we had many drown. The drowning of our soldiers was not publicized that much but we lost many to the icy water," said Dr. Parker. "Many of the wounded soldiers were in shock and it wasn't always easy to tell the living from the dead among the hundreds of bodies that lay on the beach or washed in the surf."

The biggest problem we had was a lot of casualties on the beach and trying to get them out of the way to keep track vehicles, and bulldozers, and tanks and trucks from running over the bodies that were lying up on the high water mark. And they were heavy. You'd take a man loaded down with all the combat stuff... A lot of them just drowned. They had their life belts around the belly and when they went in and inflated them, they flipped face down, and there was no way they could get back up.

Did you have any trouble yourself because you said they dropped you up to your neck in water? Yes, but I didn't activate my life belt at all. I just made it in.

Oh, so that was the problem. When they activated the life belt, it was in the wrong place and it would pitch them forward. That's right.

That's what happened at Slapton Sands? A lot of those people drowned the same way. That's right. Now a beach battalion, we'd go up there and land on the beach and then be picked up and carried back to our facilities by truck. I made several landings, two or three just being aboard as the ship's doctor, temporary duty. I had no orders to show it at all. I looked through my orders and I don't have them but I'm sure I had something to show when I went there.

We left you up to your neck in water. And then what happened after that? Well, we crawled up on the beach and made it up to the shoals. That beach was long and ...

A lot of obstacles in your way? Well, there were obstacles all over that beach, but as far as hindering my way, you could go around those physically. I mean they not only had burned out tanks, we had burned out landing craft, the whole complex. In fact, I had to make my way to the left, and I crawled along. It was rocky stuff. You couldn't dig a foxhole in that stuff. It was rocks. In other words, there was a little border around the edge of the beach up there where you could have ...

"Low Tide - American Beach Sector" by Mitchell F. Jamieson and the Normandy invasion depicted at the National WWII Memorial in Washington, D.C. The hedgehog, one of a number of beach obstacles in the tidal-flat, consisting of three steel rails welded together, was designed to rip out the bottom of landing craft during high tide. After D-Day, these steel beams were recycled by Army engineers and used to construct hedgerow cutting devices welded on the front of tanks.

A border? Well, a kind of a border. It wasn't man-made. It was a little raised area where the waves had beaten up, you know how a beach would be. And some of our troops were up there. When I got there, there was still small arms fire, a lot of 88s coming in on that beach and I had to move to the left.

And one of the first groups I ran into were a bunch of German prisoners sitting in a little pad there. I stopped by to see if they needed anything and went on up the beach. The main thing was running into people lying there, and you didn't know whether they were dead or not. And you'd go up to them and look at them and they looked pretty good on one side, you get over there, the heads blown off on the other side. So you just ran into that type of thing all day long.

The main thing was that these bodies were washing up there like cord wood on that beach and trying to clear those out. Now I had an arrangement with this commanding officer, He was a captain I think, of the DUKW outfit assigned to our beach.

And the DUKWs, I thought, were kind of a bulky looking thing and I didn't think they'd be worth a darn, but there was a time when we had some bad weather. That's the only way we could get any ammunition or food in was on those DUKWs and they could go in that water and come on out.

This guy came by and told me, "Now listen. My boys have been told when they pass you, you put up a flag, they'll stop and put your casualties on board and they'll take them to wherever you want them."

The main thing was when they got out there; they didn't know who was going to take them. There was supposed to have been some designated stuff but it was rough. So one day he came by. This was about the third day I guess, and he said he would like to see how this thing operates. I told him that I would go with him. And we got on board one of the DUKWs with a couple of casualties and we went out there and found a British hospital ship and loaded it.

The Engineer Amphibian Command opened its Headquarters at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts 10 June 1942. Provincetown Bay, near the tip of Cap Cod, was the original site of tests to determine the extent to which DUKWs could carry out in rough water the mission for which they were designed. A DUKW is a 2 and 1/2-ton amphibian truck, the workhorse of amphibian warfare. Herring Cove, Provincetown, Massachusetts, in the photo of sunset, was created as part of the Cape Cod National Seashore by President John F. Kennedy in 1961.

They were hard to load on there because it was a boat bobbing up and down with a loading platform, which is about 5 feet up and you're in a boat that's jumping up and down. You had to take at least four people to pick up a man on a stretcher and get him and the crew on board that thing to bring him on board. It was quite an operation. He got his leg caught in between part of one of the stanchions underneath that thing and broke his leg. So we had to throw him up on the boat so we lost him.

Our evacuation thing was kind of bad in that you could load an LCT or LCVP or whatever you had there. And if it broached, you had to unload it and pull them [the casualties] back out, and put them on another one. And sometimes these things got beached and they had to wait for the next tide to get them off. And later, we started having LSTs to come up and dry out. They'd just come up there and let the ramp down and wait until the tide went out. And they could unload without having to go through the water because all these vehicles were waterproofed going in.

We had to go through that whole deal of how to waterproof a jeep and a tank, and everything else. Occasionally, they would get up there and get stuck. And they hadn't dropped the rear anchor soon enough, or couldn't retract it. So if you had any casualties on board that one, you either let them stay on board if they were stable enough, or you moved the ones that you thought you could get away from there. The whole deal was to try to get as many wounded to good hospital facilities as quickly as you could.

They finally set up a big tent hospital up on top of the hill there. But that was 4 or 5 days after D-Day, and that was Army but by D plus four, we had air evacuation. They were taking them out by air, so if somebody got hurt on the fourth day, you got in the hospital in England that day. Whereas some of them got hurt on D-Day, was still on board a ship, trying to get to England, depending on the convoy, because they went back by convoy. The Navy had that wire basket you could put people in and strap them in.

The stokes litter. Yes. As far as I was concerned, that was the only thing they ought to have had because you could strap a man in it and then pull him straight up, to get him somewhere.

Normandy D-Day is portrayed at the Smithsonian and casualties are air evacuated from France. Air evacuation to the UK was to begin as soon as Allied ground forces secured airstrips usable by C-47s of the IX Troop Carrier Command. The 5th Engineer Special Brigade managed to complete a temporary airstrip near St.-Laurent. On D+4, a C-47 lifted out the first 13 patients, including 7 wounded POWs. Servicemen wounded in the morning were often on the operating table of a general hospital in the UK within 10 hours.

When you ended up on the beach there, on the first day. It must have been pretty noisy too. It must have been just a racket going on there. There was a lot of confusion, a lot of stuff going on - a lot of mobility, a lot of stuff trying to get in. As they got up those little roads, and the tanks got blown out, we didn't have any recovery stuff so they just blocked the roads. So they had to cancel the unloading for awhile because there were too many vehicles on the beach.

I know going up that beach, I saw a little Cub plane that looked like brand new, just sitting there in the waves. I don't know whether that guy forced landed or what happened to him but there was nobody in it. It was just sitting there in the waves.

The procedure, as I understand it was that once you got on the beach, you were to gather up the wounded and get them to a place out of the line of fire. And then you could take care of them, or did you just take care of them wherever they fell? We took care of them where they were, and then moved them to a place where they could be evacuated. We would try to take them to the nearest vehicle that would accept them. It didn't make any difference. Everybody was cooperative. They were trying to do everything they could.

If a boat came in and the waves hit it and it broached and got sideways, there was no way they were going to get that boat out of there right then. So you had to unload them, put them back on something else.

Right down at the end of our beach was a real cliff and in a few of the pictures that you've seen, you see some of them underneath that cliff waiting to break out of there. And that was a place of protection. However, on my beach, they told me later, they had to widen that road. And they wanted to move my evacuation station then, so I told them I'd do that. I told them to take a bulldozer up there and dig me a hole they could plant a 14 x 14 tent in, and they did that. I put sandbags around that thing. Jack Daughtrey and I put a bunch of those steel stretchers across the top of our foxhole and put sandbags on top of it, so we had a cubbyhole to stay in.

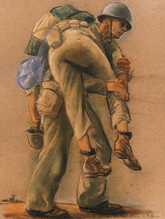

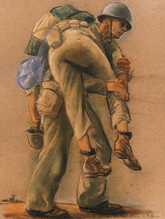

Edward P. Banham, PhM3c, a 21-year-old Navy corpsman in Dr. Parker's A-3 platoon and "Combat Convalescence" pastel of Navy corpsmen by artist-correspondent Irwin Hoffman. (Combat artwork, a gift from Abbott Laboratories, courtesy Department of the Navy - Naval Historical Center)

The boys in my outfit went up on top of there. There was a hill up there by the side of that beach which overlooked the whole beach. If you've ever seen a real combat map, you'll see they had a concrete trench on the top of it that was 10 feet deep. And it was lined on both sides with poured concrete and [the Germans] could walk around in that thing and you couldn't see them.

Every once in awhile, they had an opening with a stand, where they could put a small mortar, and they could drop these little hand mortars in there. There was also barbed wire laced across the front of that. So it was pretty protected until our Army outfit finally got in there and broke that up pretty fast. That was one of the big gun emplacements with 88s right there close to Fox Red. And they had that gun not shooting straight out but shooting up the beach.

They also had a tank trap dug. That's a big trench with sand, so when a tank ran up to it, he had to turn parallel. If he got in that thing, he could hardly get out of it anyway, but if he turned parallel, he was right in their line of sight.

And up where that trench was made of concrete, they had a silhouette of our tanks with the vulnerable parts painted in red.

They also had an old World War I French 75 sitting up in a hole up there. They dug it out and they had the armor down. They had a chain lift with which they could pull the ammunition from an ammunition depot below them.

I've got the casing from one of the French 75s and it's about 18 inches long. The projectile was about 2 feet long. And that thing was sitting right up off our beach. That big 88 that was sitting on the beach was taken out by some crazy lieutenant in a destroyer which came parallel to the beach at flank speed and got off some good shots. That kind of stunned them a little bit. Then some Army combat infantry went up there with their satchel charges, threw them in there, and blew up the whole thing. We got a bunch of prisoners out of that one.

Did you see any of that happening? I didn't see it but I heard it.

You were down in your bunker by then? Well, I'll tell you. The Texas was firing 14-inch shells over us all day. That was something to hear. You could hear them rumble. But the darndest thing was in the mornings, later on when you could look up there and see these Flying Fortresses [B-17s], or whatever the big one was at that particular time, in formation just as far as you could see.

"The Wounded Don't Walk" pastel by Irwin Hoffman and later during the Normandy landings, above Omaha Beach, a medical aid station of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, 61st Medical Battalion.

But during the initial invasion, the Air Corps missed our beach. They were supposed to put a bunch of potholes in there, and we were afraid we were going to have to worry about those potholes on the beach, and then looking for foxholes to stay in, but there weren't any. But on Utah Beach, where they did have pre-elimination air cover, they had very few casualties. But the bombers that were supposed to take care of our beach had bad fog and a lot of reasons for not hitting that beach. They sure missed it.

So Easy Red was on Omaha? Yes.

And you say it was toward the left end of Omaha? It was the whole beach area. I don't think they ever hit any of that beach, to tell you the truth.

No, they never hit it at all. They dropped their bombs inland apparently. They couldn't see where to drop them, so they just dropped them. Yes, they just dropped them and got out of there. But on Utah, apparently they could see all right and they did a good job.

So, things hadn't really quieted down all day. Oh, it was rough and I don't even remember when day ended and night started, to tell you the truth. And I guess I slept, I don't know. But we stayed busy. The next morning, we were still moving them out. For about 4 days we worked to get people out of there, and then later they started air evacuating, and they had that little hospital set up on top of there. We had a whole field hospital with nurses and everything up there. But that was later on.

That was later, and you couldn't do any kind of definitive care, you were just doing first aid kind of stuff. That's exactly right, and that's the reason now they tell me that this whole operation is going to be taken over by the Navy Seals, and they'll just train the pharmacist mates to do a little bit better. So, I think that's probably correct.

So the corpsmen you had with you, were pretty well trained though. They were well trained. They did an exceptional job. They did everything they were supposed to do, and really more then I could have expected.

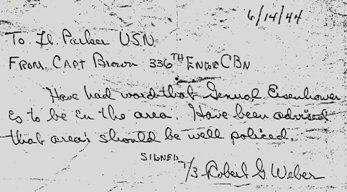

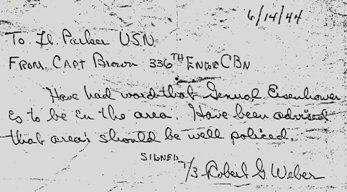

The 5th Engineer Special Brigade was organized in the United Kingdom on 12 November 1943 from the 1119th Engineer Combat Group with three attached engineer combat battalions - the 37th, 336th, and 348th. The combat battalions of both the 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades had amphibious training on the Atlantic coast at Fort Pierce, Florida, the US Navy's Amphibious Training Base. With a total strength of 42 officers and 362 enlisted men, the 6th Naval Beach Battalion was attached for the 6 June 1944 cross-Channel attack as follows: Company A - 336th Engineer Combat Battalion, Company B - 348th Engineer Combat Battalion, Headquarters and Company C - 37th Engineer Combat Battalion.

What happened after that? Where did you go after D-Day? How long were you there before you went back to England? Well, I think it was on June the 25th or something like that, we went back to England. And we stayed around and got on board an Army troop transport and I don't remember the name of it, but anyway, we ate well, we had good accommodations. They took us back into New York. We had about 3 or 4 days liberty, and then we got orders.

I was sent back to Fort Pierce to be part of that ship's company there. And about the time I got orders... In fact, while I was down there, I was going over at night with an ambulance to the north shore, where they were doing the training for the Scouts, and Raiders, and the Rangers; where the Seabees would put up some obstacles, and they would come out of those boondocks down there, had to paddle all the way out that river, cross that jetty with rubber boats, and then paddle a good ways up and immediately come in and plant their charges on the beach. I was in an observation tower down there with an ambulance, just sitting there just in case they had casualties.

We never had anything to do, just sit there and watch them come in but then, I got my orders to go to Panama City, Florida, with a ship's company shaking down LSTs. I stayed there until the last LST was down.

Then they sent me to the Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. I got to Guam and ended up with an outfit. If it hadn't been for the A-bomb, I'd have been going into Japan, but that saved my life, I'm sure. So I ended up with the Marine Corps in Tientsin, China, real good duty with no problems.

Paris was liberated in August 1944. After the Allies fought across Europe, the doors to the Nazi death camps were opened and Berlin fell in May 1945. The atomic bombs were dropped in August 1945, ending the war. World War II left bitter memories in the mind of Dr. Lee Parker. On 6 October 1944, his younger brother, Lieutenant Jack S. Parker, was KIA near hill 99 in Italy. Although Jack Parker was a highly decorated officer, his death demolished the spirit of the Parker family. Dr. Parker told Navy medical historian Jan Herman, "It's bad to see a 17-year-old come up with the loss of a leg, the loss of an arm, certainly the loss of life. War is hell. It's not to be glorified in any way."

That was after the war was over? Yes.

Well, you certainly saw a lot of stuff there. You were quite a busy doc, weren't you? I stayed busy, sure did. I'm afraid I'm not much help to you.

No, you've been very helpful. You know, everybody saw that event from a different perspective. Everybody was in a different place and they all saw something different. So, when you put it all together, you end up with a clear picture as to what happened. I'll tell you, this report that I'm sure you got from Ken Davey, about this news report on the invasion on the beach, I thought was about as good as you could come up with. You've got a hold of Ken haven't you?

Yes, oh yes. Well, there is a book, The New Yorker, War Pieces, by A. J. Liebling, Cross Channel Trip. That's about as good a write-up as you can get on that whole thing. Ken got it because his father was named in it, but he showed exactly what happened. It's about as good as you can get.

I've interviewed some other folks who were in an outfit that trained at Lido Beach. It was called Foxy 29. It was a bunch of physicians and corpsmen who went over, and they were responsible out on the LSTs, for evacuating the patients. And they saw it from a different perspective also.

Dr. Groom lives down in Jacksonville. We interviewed him and recently, I spoke with him again. And of course, you know, this whole bit with "Saving Private Ryan" has refocused attention on all of that. Oh, it sure has.

Did you see the film? Yes.

Did you think it was accurate? Thought it was very accurate. Better than I could have hoped for. They did a good job, and I don't see how they got all that material together to see the shots that they did on the beach because they looked good.

Yes. That was pretty much the way you remembered it then? Yes, that's exactly the way it was.

I guess that's a credit to Spielberg for doing a good job. Very much credit to him because they did a good job.

*****

Dr. Parker's 1999 BUMED interview resulted in a return trip to Normandy for on-sight filming of Navy Medicine in Normandy, part of a documentary series of "Navy medicine in World War II" from Pearl Harbor to final victory. Historian and film maker Jan Herman recalled in 2011, "Some of the most memorable recollections are indeed the location 'shoots' with the veterans. How can I ever forget walking the hallowed ground of Omaha Beach with Dr. Lee Parker, a D-Day veteran? I asked if he recalled where he came ashore on that fateful day 54 years before. He peered to our right toward a headland jutting from the Normandy coast, and then, as if to get his bearings, turned to gaze at the high ground behind us. On 6 June 1944, that bluff bristled with German guns that rained death upon American soldiers and sailors as they departed their landing craft. He then exclaimed, 'Right here! This is where I came ashore. They told us there would be plenty of craters to take shelter in after they had bombed the place but there weren't any. They missed that beach.' He recalled the horrifying sound of the German '88s firing point-blank at the incoming landing craft and taking a terrible toll in lives. The Normandy American Cemetery, the final resting place for more than 9,000 servicemen, now occupies that bluff above Omaha Beach. A day later, as we slowly walked among the white marble crosses and Stars of David, Dr. Parker spoke softly about sacrifice and his own miraculous survival. His brother died on another European battlefield. He then abruptly changed the subject. The memories had become too overwhelming."

Back to Top

Back to Top